Why Established Companies Don’t Need To Act Like Startups

Innovation has become an imperative for large established companies. This is due to the threat of disruption from startups and the ever changing technology landscape. While most corporate leaders would love for their companies to “act like startups”, this is not always a realistic aspiration. Most large companies have a core business to run, in addition to developing new innovative products. In our new book The Corporate Startup, we argue that established companies should not try to act like startups. Rather, they should build internal innovation ecosystems with products and services that are at different points of their lives. Below is an extract from the book describing the five principles for building corporate innovation ecosystems. The Corporate Startup is now available for purchase here.

__________________________________________

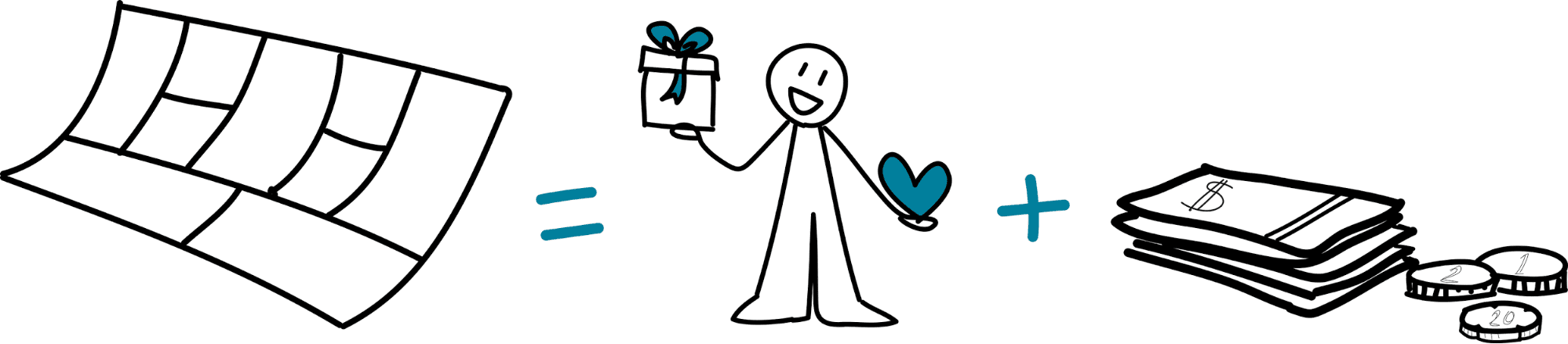

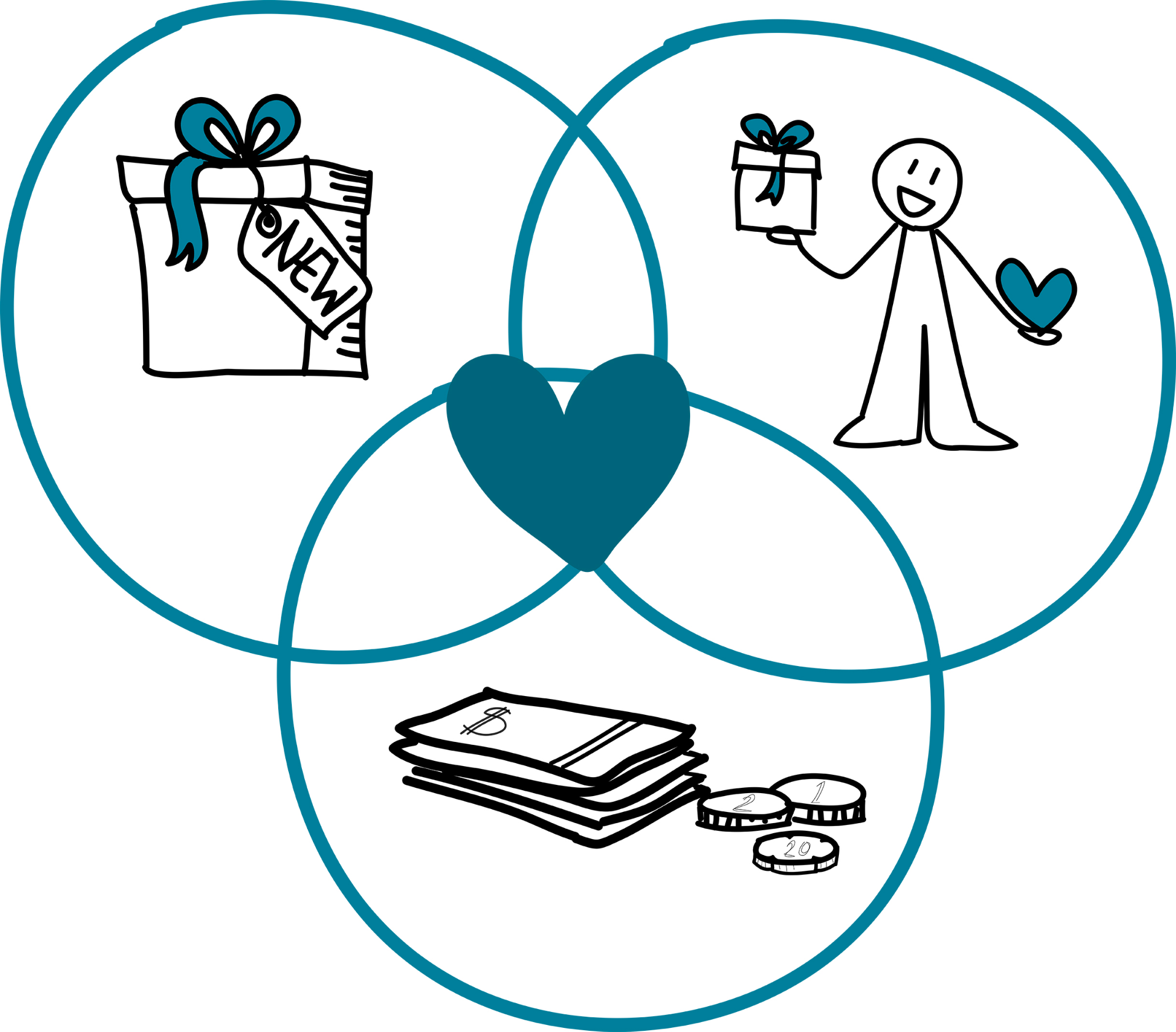

A good place to start is by providing a clear definition of what innovation is. Innovation is often simply defined as a novel creation that produces value. From our perspective, the concept of innovation as distinct from creativity involves three important steps. The first step involves the novel and creative ideas that are generated through various methods that trigger insights. The second step is ensuring that our ideas create value for customers and meet their needs. The final step involves finding a sustainable business model. This part of the journey involves ensuring that we can create and deliver value to customers in a way that is sustainably profitable.

These steps make clear that it is the combination of great new ideas and profitable business models that defines successful innovation. As such, our corporate startup definition of innovation is:

The creation of new products and services that deliver value to customers, in a manner that is supported by a sustainable and profitable business model.

This definition lays bare what the role of innovation in any organization should be. It is not to simply create new products and services. New products may be part of the equation but the ultimate outputs of innovation are sustainable business models. A business model is sustainable when our novel creations deliver value to customers (i.e. when we are making stuff people want); and when we are able to create and deliver this value profitably (i.e. we are making some money). Without these two elements, a new product cannot be considered an innovation. It is simply a cool new product. It might be the coolest thing since sliced bread – the most creative product ever made – but if it doesn’t deliver value to customers and bring in profits, it is not innovation.

Our definition of innovation also provides us with a clear job description for corporate innovators. Your job is to help your company make money by making products that people want. The sweet spot is when your creativity meets customer needs and you can make money from serving those needs. It is also important to clarify that not all forms of innovation will be focused on new products or services. It is possible to innovate around internal business processes that are not directly experienced by customers. This form of innovation is not an explicit focus of this book. But, even for these forms of innovation, the delivery of sustainable value is still an important principle.

Red Pill – Blue Pill

From the definition above, it is clear that the only indisputable fact is that innovation should be managed via different processes to those that are used to manage core products. How these processes are instantiated depends on the company, how much management buy-in you have and the innovators’ appetite for corporate politics. Sometimes it can be very clear that you will never get full executive endorsement for innovation. The executives are too focused on cash cow products and the best you can hope for is support from a handful of visionary leaders within your business. In these cases, innovators might consider leaving the company for greener pastures.

Alternatively, innovators can start a guerilla movement. A corporate innovation insurgency, so to speak. Tristan Kromer, who is a great innovation ecosystem designer, has two recommendations on how innovation ecosystem designers could manage such a movement. First, Tristan suggests that innovators should lower the costs of innovation. If they do this successfully, then they will hardly ever need high level budget approvals. The lean startup, design thinking and customer development toolbox provides great methods for lowering the costs of innovation.

Every now and again, innovators will need to surface within the company in order to get investment for their ideas to be taken to scale. It is also possible that things will get to the point where the costs of innovation can no longer be kept low. For this, Tristan recommends that innovation teams find diplomats. These are individuals who will do the hard work of corporate politics and smoothing the path for innovation projects. A diplomat is usually someone who is well-connected and respected in the business, who can work outside of normal bureaucratic channels to call in favors and get things done. Without a diplomat, most guerilla projects are dead on arrival.

Guerilla movements have been known to succeed, sometimes. Nevertheless, this is our least favored method. We have found that guerilla movements are too difficult. Teams are always watching their backs for unexpected impediments to their work. And if they lose their management sponsor or diplomat, then their innovation efforts are easily placed in jeopardy. So while guerilla tactics can work, they also have a really high mortality rate for product ideas. This is the reason we favor a full frontal assault on the company to change its ways of working.

With a full frontal assault, innovators tackle the hard questions upfront. Long-term sustainable innovation is only possible within a supportive ecosystem. As such, it is important to get top level executive and middle manager buy-in. This air-cover will help in future situations when there is need for support and resources. Regardless of whether the innovation lab is external or part of an internal process, strategic alignment is key. Innovation ecosystems can only be created when we do the hard work of changing and adapting the company’s capabilities to ensure that they fully support our chosen innovation approach. The principles for building this innovation ecosystem are the focus of this book.

The Five Principles of a Corporate Innovation Ecosystem

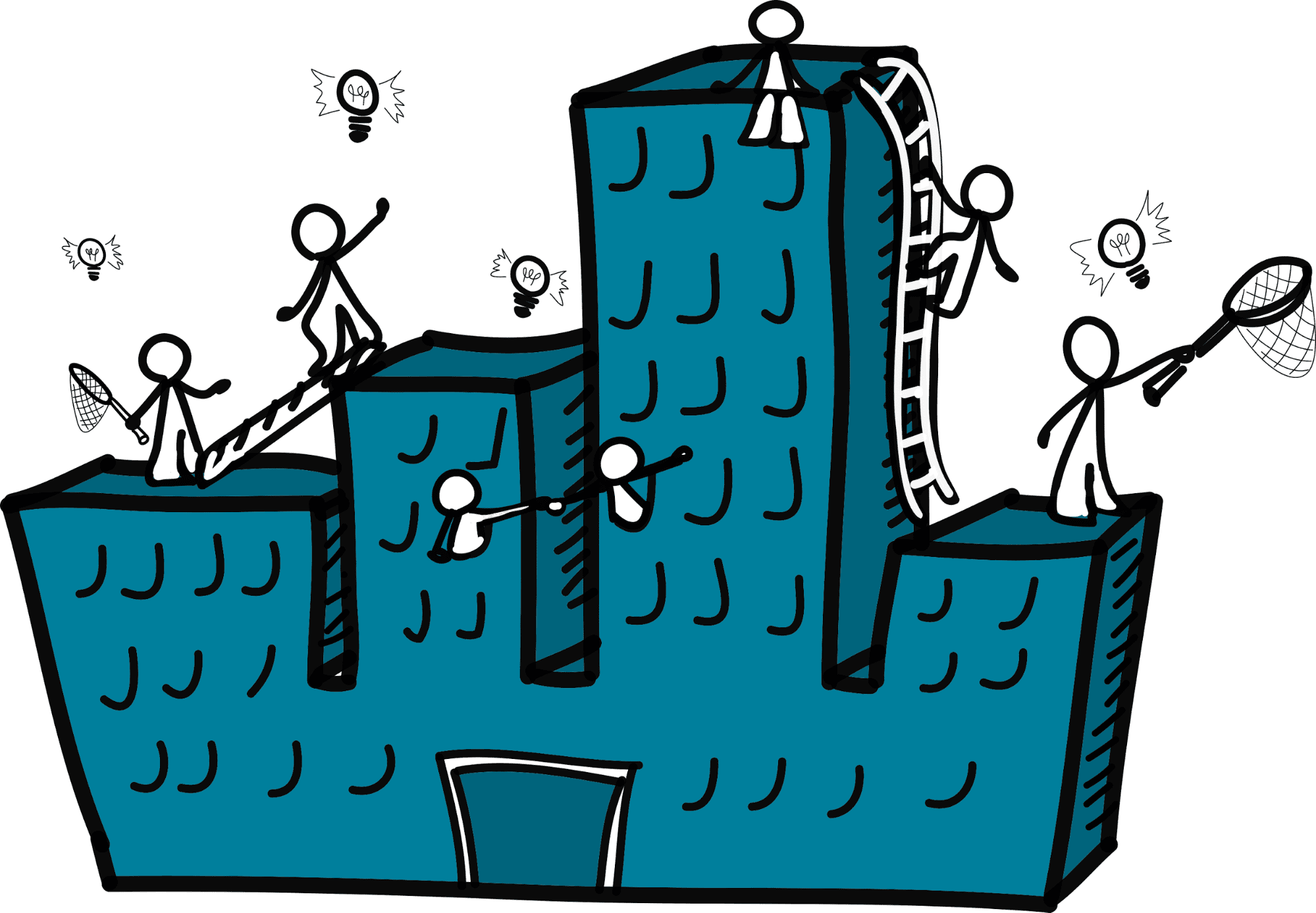

Successful innovation necessitates interactions among multiple actors from multiple parts of a company. In the journey from ideation, product creation, first customer sales, growth and scale, multiple parts of the organization are inevitably involved in innovation. This is why organizational alignment around innovation is critical. Companies need to create an internal process that:

- Facilitates the serendipity that creates sparks of creative ideation.

- Captures and tests the outputs of this creative ideation.

- Transforms ideas into successful products with profitable business models.

This means that organizations need to be designed to create and benefit from serendipity. The goal of this book is to articulate the principles that inform how organizations manage these innovation complexities. We strongly believe that principles trump tactics. It is, ultimately, up to each organization to adapt these principles and apply them to its business, strategic goals and context. The five principles for building corporate innovation ecosystems are as follows:

Innovation Thesis

We believe that innovation must be part of, and aligned with, the overall strategic goals of the company. This is important when it comes to later transitioning innovation projects into the core product portfolio. Just like venture capital investors have investment theses that specify the types of startups and markets they invest in, every large company must have an innovation thesis. An innovation thesis clearly sets out a company’s view of the future and the strategic objectives of innovation. For example, an established software company can take the view that driverless cars are the future and they want to get in that market early. Their innovation thesis will be that they invest mostly in new ideas that bet on that future (i.e. software products for driverless vehicles). In this regard, an innovation thesis sets the boundaries or guard rails concerning the innovation projects the company will or will not consider. In addition to this deliberate strategy, the company must also use its innovation process as a source of emergent strategy that is responsive to changes in the market.

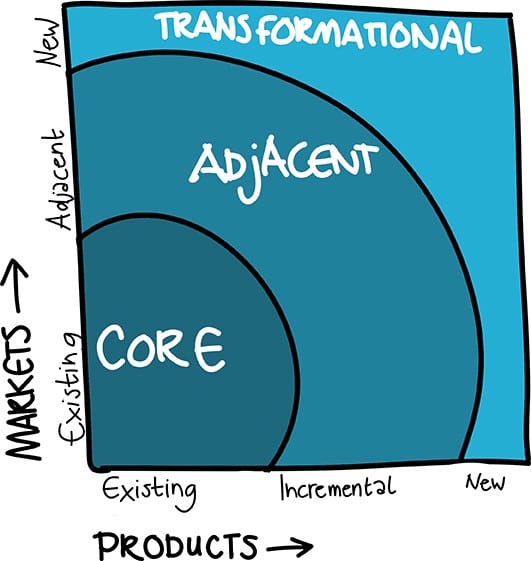

Innovation Portfolio

To achieve its innovation thesis and strategic goals, an established company should then set itself up as a portfolio of products and services. This portfolio should contain products that cover the whole spectrum of innovation; i.e. those that can be classed as core, adjacent and transformational. The portfolio should have early stage products, as well as mature and established products. A company may also consider having in its portfolio disruptive products that are aimed at lower-end or emerging markets. The goal is to have a balanced portfolio in which the company is managing various business models that are at different stages of their lives. The balance of the product portfolio should be an expression of the company’s overall strategy and innovation thesis.

Source: Nagji, B., & Tuff, G. (2012). Managing your innovation portfolio. Harvard Business Review, 90(5), 66-74.

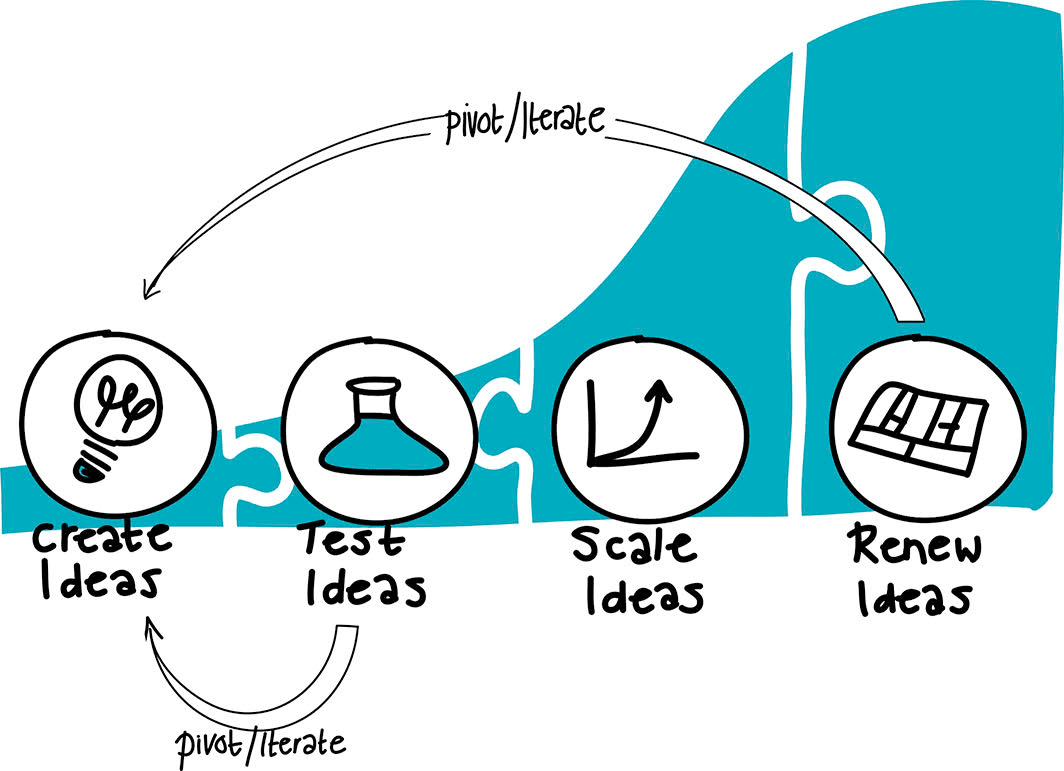

Innovation Framework

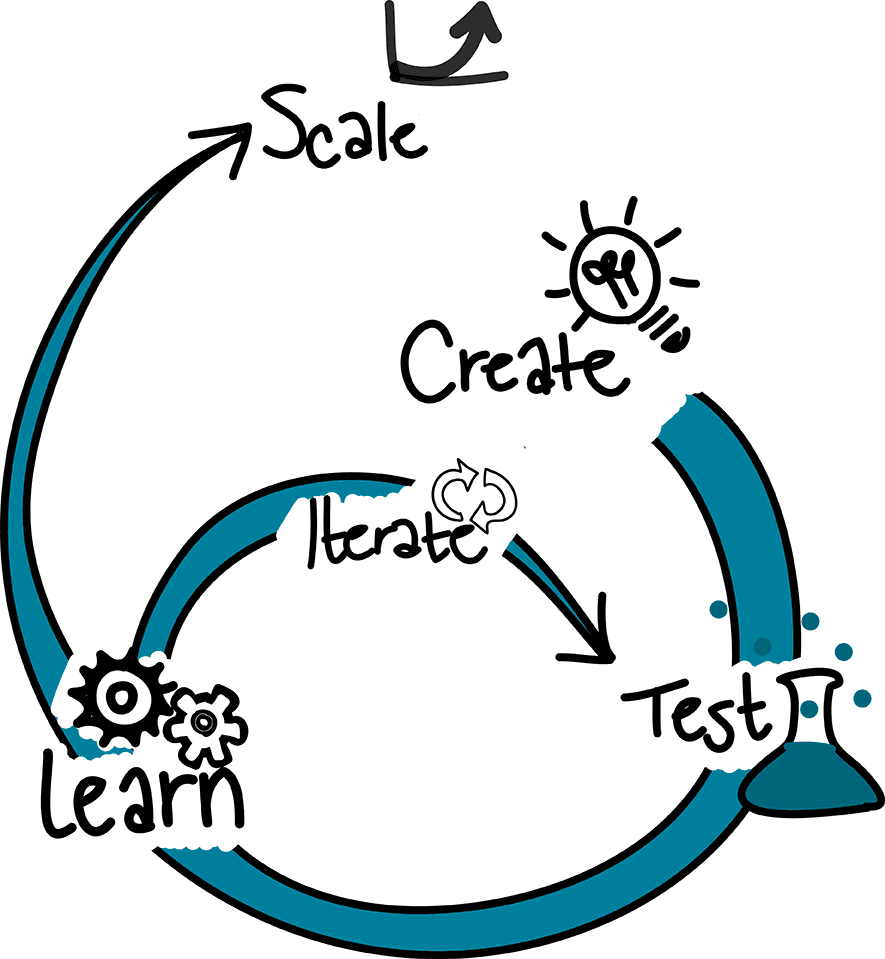

In order to execute on its thesis and manage its portfolio of products and services, the company needs a framework for managing the journey from searching to executing. There are several examples of innovation frameworks; for example Ash Maurya’s Running Lean framework and Steve Blank’s Investment Readiness model. At Pearson, Tendayi has been part of a team that has developed the Lean Product Lifecycle, which is an award winning innovation management framework. All these frameworks can be synthesized into the three simple steps for innovation; creating ideas, testing ideas and scaling ideas. Every now and again, a company may decide to refresh the business models of its existing products through renewing ideas. Having an innovation framework provides a unifying language for the business. Everybody knows what phase each product or business model is in. This then provides the basis for how a company can manage its investment decisions and product development practices.

Innovation Accounting

With an innovation framework in place, the company now needs to make sure they are using the right investment practices and metrics to measure success. Traditional accounting methods are great for managing core products. However, when managing innovation, different sets of tools are needed. We propose that companies should use incremental investing based on the innovation stage of their products. This approach is based on Dave McClure’s Moneyball for Startups. We also propose three sets of innovation KPIs that companies should be tracking:

- Reporting KPIs focus on product teams, the ideas they are generating, the experiments they are running and the progress they are making from ideation to scale (e.g. assumptions tested and validated).

- Governance KPIs focus on helping the company make informed investment decisions based on evidence and innovation stage (e.g. how close are the teams to finding product-market fit).

- Global KPIs focus on helping the company examine the overall performance of their investments in innovation in the context of the larger business (e.g. percent of revenue in the last 3 years).

Innovation Practice

In addition to correctly managing investments in innovation, the way in which product teams develop their products has to be aligned to the innovation framework. Pearson’s Lean Product Lifecycle is accompanied by a great playbook that provides guidance to product teams as they search or execute on their business models. Adobe’s Kickbox provides similar guidance, tools and resources. The core principle for innovation practice is simply that no product can be taken to scale until it has a validated business model. As such, during the search phase the job of innovators is to validate their value hypotheses (i.e. does our product meet customer needs?) and their growth hypotheses (i.e. how will we grow revenues and customer numbers?). This process requires that teams validate both the attractiveness of the product to customers and the potential profitability of the business model. A key part of this innovation practice is the idea of a network or community. Companies have to create and support communities of practices that interact regularly and share lessons on best practice. This ensures that innovation skills are shared and developed as a human capability across the company.

It’s An Ecosystem

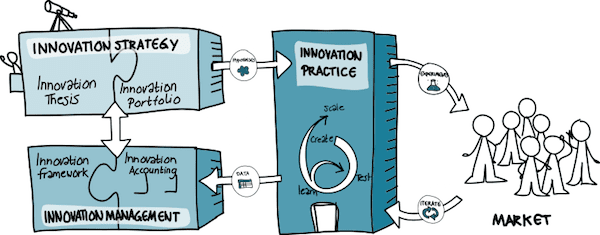

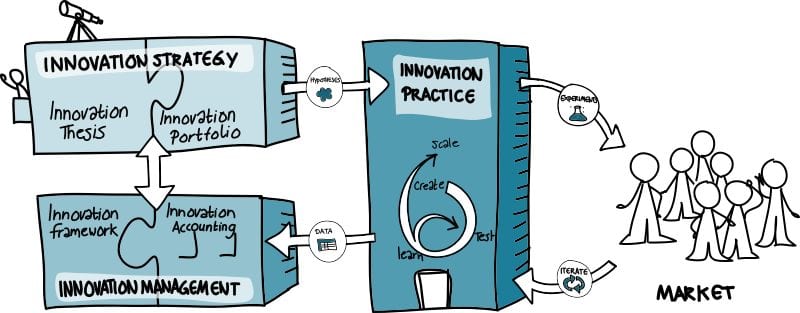

These five principles combine to help create an innovation ecosystem. The first two principles (thesis and portfolio) focus on innovation strategy, the next two principles (framework and accounting) focus on innovation management and the last principle is where rubber meets the road and the company begins interacting with customers and validating business models. Most innovation labs have tended to just focus on this last part (innovation practice). But the truth is that without a supportive ecosystem in place, products coming out of innovation labs will have high mortality rates. This is why applying all five principles is important.

As you can see above, these elements are interconnected; each representing a create-test-learn loop of its own. To the extent that strategy informs investment decisions, the success of these decisions in turn informs strategy. To the extent that investment decisions impact innovation practice, innovation practice produces learnings that inform investment decisions and, in-turn, inform strategy. This is an innovation ecosystem at work. Each interconnected piece is responding to data from the other pieces. Such a holistic approach allows companies to innovate like startups, without having to act like startups.

About the Author

Tendayi Viki is strategy and innovation consultant. He holds a PhD in Psychology and an MBA. He has worked with several large organizations including American Express, Standard Bank, Pearson, World Bank, Whirlpool, Airbus and The British Museum. He is the author of two books based on his research and consulting experience, The Corporate Startup (with Dan Toma and Esther Gons) and The Lean Product Lifecycle (with Craig Strong and Sonja Kresojevic). Tendayi co-designed Pearson’s Global Product Lifecycle which is a lean innovation framework that won the Best Innovation Program 2015 at the Corporate Entrepreneur Awards in New York.